Chapter 2. The Hulks, Voyage and Assignment

Satisfied that every practicable exertion was made for their comfort, and cheered by the prospect of a speedy termination of the voyage, the spirits of the Convicts continued buoyant to the last.

-Thomas Logan, RN; Surgeon-Superintendent, Proteus

The character that our Captain and Doctor gave us excellent and the people of Sydney considered us to be downright honest men a valuable qualifycation here.

-Letter from Robert Mason, transported Swing-rioter, on arrival in Australia

Convicted Swing-rioters sentenced to transportation were sent from the county gaols to the hulks before banishment, at the first available opportunity, to the Australian colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemens Land or to Bermuda. The transport vessels listed in Table 1, which took the convicted Swing-rioters to Australia were ordinary British merchant ships chartered from their owners and subjected to Royal Navy inspection. During the voyage the convict prisoners on each transport were under the care of a surgeon-superintendent appointed by the Royal Navy who had absolute control over the transportees under his charge. The surgeon-superintendents were usually, but not always, naval surgeons who earned promotion by delivering the convicts under their charge to their destinations alive and in good health and neither the ships' captains or officers in charge of the guard could countermand their instructions. Much depended on their quality and their consideration for the prisoners under their charge but generally speaking the surgeon-superintendents were efficient and mindful of the convicts' well-being.

Seven men, convicted at Canterbury, Kent on 25 November, arrived on board the prison hulk York at Portsmouth on 3 December 1830 and were put on board the transport vessel Eliza twenty-five days later. They were followed on 17 and 18 December by fourteen men convicted at Chelmsford, Essex, who were transferred to the Eliza after ten or eleven days on the hulk. Charles Dunnett, also convicted at Chelmsford, remained on the hulk for thirty-eight days before going to the Eliza possibly because he was at first considered unfit to undertake the voyage. As he died shortly after arrival in Van Diemens Land it may be doubted that he was ever in a fit state of health for transportation.1

Although all the Swing-rioters sentenced to transportation embarked on transports via one or other hulk their stay on the hulk was usually less than one day and often limited to the time they spent walking across its deck to the waiting boats which took them to the transport. Possibly their limited stay on the hulk was due to a wish to get rid of them as soon as possible but more likely it was designed to keep them from the company of hardened criminals aboard the hulks. After the Canterbury and Chelmsford men were loaded Swing-rioters arriving at the hulk were transferred immediately, or after one to two days only, to the Eliza and later to the Eleanor or Proteus but common felons who arrived at the same time as the Swing-rioters remained on the hulk to be transported often as much as six months later.

After Eleanor sailed no transport was immediately available and Swing-rioters awaiting transportation stayed on the hulk for an average period of thirty-three days until Proteus came to anchor in Portsmouth Harbour and was made ready for loading. Not enough convicted Swing-rioters were immediately available to make a full complement of transportees on the Proteus so fourteen convicts, selected from amongst common felons of better than average character, were added to the ninety-eight convicted Swing-rioters already loaded on the transport to make up the deficiency.2 The prisoners embarked on 6 April 1831 for a voyage to Van Diemens Land which lasted exactly sixteen weeks (14 April to 3 August 1831). On board the Proteus, a barque of a mere two hundred and fifty tons, there was a guard of the Fourteenth Regiment, a detachment of Sixteenth Lancers, some free passengers and the crew in addition to the one hundred and twelve transportees which was a huge load for a small vessel which made no ports of call from leaving England until it arrived in Van Diemens Land. There were no deaths among convicts, guard or passengers on the Proteus but one crew member died of unstated cause on the voyage.

Swing-rioters sent to Australia on vessels otherwise carrying only common felons were held for up to two years on a hulk before sailing and were the most disadvantaged of the transported rioters. They were denied the companionship of their comrades on the voyage and were disadvantaged after arrival in Australia by not sharing the emancipation privileges given to those Swing-rioters who came on the three principal transport vessels. On their transports they were the shipmates of criminals transported for crimes such as murder, manslaughter, rape, stealing from the person, highway robbery, approaching with intent to rob or receiving stolen property. Although uncomfortable for them at the time their experiences on the voyage no doubt helped to prepare them for later association with the former criminals who became the ancestors of many of today's Australians.

No account of the sixteen week, non-stop, voyage of the Eliza has survived, but the vessel is known to be the only convict transport ever to arrive in Australia, or elsewhere, carrying convicts all of whom had been charged with offences alleged to have been committed during the Swing Riots. Accounts, based on the surgeon-superintendent's reports, of the voyages of the convict transports Proteus, Mary, Lord Lyndoch, and Gilmore (to Van Diemens Land) and Eleanor and John (to New South Wales), all of which had at least one Swing-rioter on board have been published.3 The surgeon-superintendent's report for Eliza is not to be found in the Tasmanian Archives and its whereabouts, if it is still in existence, is unknown.

The Eleanor should, like the Eliza, have arrived in Australia carrying an all Swing-rioter convict cargo but three common felons convicted in South Africa were embarked when the transport called into Capetown to take on provisions while en route to its destination.

In the journal of Thomas Logan, Surgeon-Superintendent of the Proteus, he remarked of the vessel and the convicts under his charge:4

The Proteus was a teak ship of 253 tons: the number of Convicts embarked was one hundred and twelve. They were a part of the ignorant & misled Englishmen termed Rioters, who had overthrown order, & violated the public security. Most of them were men from the country; farm labourers; only a few were artisans. Generally speaking they had the sturdy build of labouring men. Their awkwardness & stiffness were such that I became desirous of removing the embarrassment which their Irons but too evidently occasioned - not to speak of the danger of accidents to which they exposed them. They were all removed before leaving Portsmouth nor did subsequent experience teach me that this act of consideration & beneficence had exceeded the limits of just prudence.

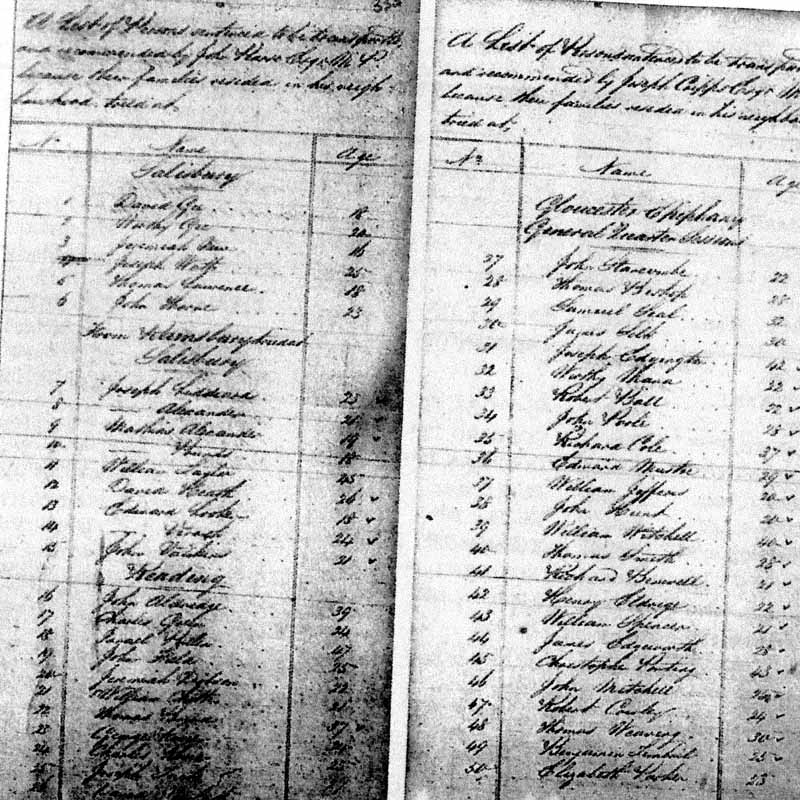

The prisoners made the journey without being ironed, except in a few instances when short periods in leg irons or handcuffs were used as punishment for minor infringements. See Figure 2.

Logan recognised that the ninety-eight Swing-rioters under his charge were not a typical group of transportees; his Names of Convict Rioters per Proteus ... had an added List of the Prisoners per Proteus who are Felons which included the names of all fourteen non Swing-rioters on board. The felons were the worst offenders during the voyage; they amounted to just over twelve percent of the prisoners but were charged with fifty-eight percent of the offences punished by handcuffing or putting in leg irons. Of a total of eighteen offences which were punished by ironing twelve were committed by one of the ninety-eight Swing-rioters and six by one of the fourteen common felons. Thus about twelve percent of the rioters were ironed at some stage during the voyage compared to forty-three percent of the common felons.

A total of sixty-eight convicts, including sixty swing-rioters, attended for treatment over periods of one to one hundred and three days and perhaps some who weren't ill at all attended sick muster out of pure boredom. In fine weather the men were kept on deck as much as possible and, without leg irons, they were presumably free to move about a little on deck so long as they did not impede the working of the ship. In foul weather there was nowhere to go except the prison where the space between decks allowed only the shortest men to stand upright. All of the Proteus transportees arrived in Van Diemens Land in seemingly good health, except for two who went to hospital on arrival; one with phthisis (advanced tuberculosis), the other with scurvy. As well as being better fed than they were as farm labourers the convicted rioters almost certainly received better medical attention as prisoners than they had as free men.

Surgeon-Superintendent Logan treated one hundred and four cases for an average of above ten days each during the sixteen week voyage. He also treated members of the guard and presumably crew and passengers as well, for the Proteus carried no other surgeon. Extracts from Surgeon-Superintendent Logan's Sick-books of Guard and Prisoners per Proteus are given in Tables 3 and 4. Obviously the voyage was no pleasure cruise, as is evident from the following extract from the surgeon's report:

The Proteus was a small ship, so small that, from Portsmouth to the Derwent we durst not, for fear of shipping water, venture to take the scuttles out for air. Except in the finest weather the sea washed over the upper deck. It is not necessary to say what happened when it blew strong. It was necessary to batten down the main hatch and so keep it, nearly all the time we were gaining our grand line of east longitude. By reason of this the prison was dark, except near the fore & after hatchways. The bad weather which rendered it necessary to batten down the main hatch likewise caused great leakage into the prison. It will not be difficult to fancy how bad was the abode of the Convicts during this part of the voyage.

The square or rectangular openings in the sides of old time sailing ships which allowed ventilation were called scuttles but from the end of the seventeenth century the structure, or lid, which covered an opening was also called a scuttle. To take the scuttles out for air meant removing the lids for ventilation purposes and simultaneously admitting light. Gaining our grand line of east longitude referred to the easterly passage of the Proteus across the Southern Ocean. The South Atlantic crossing was accompanied by strong westerly winds which in July and August would have been very cold and the convicts were of necessity kept continually below decks for safety even though the surgeon-superintendent would have preferred otherwise:

In regard to the health of the convicts themselves, I deem it of paramount importance that they be kept the whole day on deck, except in bad weather. Without this they must become sickly. Allowed to be below they crawl into their berths & snore away their existence, or work mischief, & create dirt & disorder. Their is something morally as well as physically salubrious in the open air. All meanness and vice naturally fears the broad day light. Convicts especially, should be kept in view of Heaven as much as possible

The surgeon-superintendent's report suggests that he rather regretted not having the opportunity to demonstrate his prowess by dealing with more serious cases of illness than those which occurred during the voyage although, with some justification, he believed himself to be responsible for the absence of such cases:

I am persuaded that their exemption from sickness depended much on that heart-ease & mental elasticity which all men feel, when convinced by experience, that, whatever be their hardships, they have at all events been treated with justice and humanity .... If, for one fourth of the voyage, the situation of the prisoners was dismal, the remainder of it was performed in what, in order to be fair, I must call favourable circumstances, everything considered.

The prison was rather low perhaps, but otherwise sufficiently roomy. In the northen and southern temperate zones the thermometer generally speaking thro'out the voyage, ranged from the 50 to the 60 degrees Farenheit, mostly perhaps towards the 60th. These alone were circumstances very favourable to health .... Satisfied that every practicable exertion was made for their comfort, & cheered by the prospect of a speedy termination of the voyage; the spirits of the Convicts remained buoyant to the last. Scurvy did never the less begin to appear. Fortunate & consoling therefore was it, that at this period, the Proteus arrived at her destination.

Generally speaking both guard and prisoners suffered mainly from upper respiratory tract infections with scurvy making its appearance in both groups towards the end of the voyage. Some of the Proteus guard, however, had venereal diseases which were diagnosed shortly after leaving England; and similar diseases were found amongst the Eleanor guard and in one of their wives. The sleeping space in the Proteus prison was, presumably, as limited as that in the Eleanor prison which was described by its Surgeon-superintendent, Peter Cunningham, as:

Two rows of sleeping berths, one above the other, extend on each side of the between decks, each berth being six feet square, and calculated to four convicts, every one thus possessing 18 inches (46 cms!) space to sleep in.5

John Simon Clarke, a twenty-one-year old Huntingdonshire man was diagnosed with phthisis (advanced tuberculosis) during the voyage and was one of only two Proteus transportees hospitalised after the vessel's arrival in Hobart. The other was William Hughes, also from Huntingdonshire, who was suffering from scurvy. Surgeon-Superintendent Logan took the opportunity, before leaving Hobart for Sydney on the Proteus, to visit the stricken John Simon Clarke in hospital and wrote:

The last time I saw him Death was already written in large characters on his countenance. He was bent with weakness, could scarcely walk, hectic consumed him, and at night he soaked in drenching sweat.

Clarke was tentively appropriated to the service of David Gibson in Northern Van Diemens Land but never became an assigned servant. It is a matter of some surprise that he lived for nearly twelve weeks after arrival in Van Diemens Land before dying on 2 October 1831 in hospital.6 Three other Proteus men also died shortly after arrival:

- John Annetts on 21 September7

- the seventeen-year-old Jeremiah New, the youngest Swing-rioter on the ship, on 18 October 18318

- John Moody who died accidentally in the service of the man to whom he was assigned on 23 December 1831.9

The first two both possibly died from tuberculosis contracted before leaving England.6 Annetts was recorded as suffering from Cephalia on 20 June and from Contusio on 30 June, New from Catarrhus on 10 April and from Cynanche tonsil on 28 June 28 1831.

Swing-rioters transported to Van Diemens Land per Eliza who died in 1831 were:

- Stephen Moon on 19 June10

- Charles Dunnett on 4 Jul11

- Peter Houghton on 14 July12

- William Rogers on 8 September13

- George Jenman on 26 September.14

All certainly or most probably died from tuberculosis. As the Eliza surgeon-superintendant's report has not been located no information about the medical history of those men during their voyage to Australia is currently available.

The John surgeon-superintendant's report included details of attempts by convicts to set fire to the transport's prison while at sea on the night of 25 March 1832. The men who had attempted to fire the prison were detected and punished but another prisoner, John Clifton, was apparently heard to remark that he wished the ship was on fire from stem to stern. Rightly or wrongly Surgeon-Superintendent James Lawrence believed that Clifton had been concerned in the kindling of the fire and, as punishment, ordered him next morning to walk the deck with a bed on his back for two hours. Clifton was leg-ironed while undergoing his strange punishment but the ship's master thought that he was only wearing one leg-iron. However, instead of walking he was observed running, although he apparently carried the bed only during the final fifteen minutes of his punishment.

When his ordeal concluded Clifton sat on the deck where he was later found cold and shivering before being carried below where he died almost immediately. In reporting Clifton's death after arrival of the transport in Sydney Surgeon-Superintendent Lawrence admitted that Clifton had been exhausted a good deal by his punishment but asserted that his death was due to his while being the state of exhaustion referred to, and unknown to me, drank about two quarts of cold water which caused his death.

At the subsequent enquiry into Clifton's death no blame was attached to any person on account of his sudden death nor was the legality of his punishment questioned. The John was carrying only one Swing-rioter, who was in no way concerned in the attempt to fire the prison, but Swing-rioters who committed offences on other transports were fortunate to have more humane and competent surgeon-superintendants than was Lawrence.

Any valuables held by the convicts on arrival were taken from them and held until their emancipation and any money in their possession was banked on their behalf at five percent per annum interest and held until they could legally own property; in actuality when their sentences were complete but in practice, in Van Diemens Land at least, upon receipt of a ticket of leave. The most wealthy convict transport arriving in Van Diemens Land in 1831, in terms of money held by the prisoners, was the Proteus with Eliza the next most wealthy. See Table 5.

However most arriving Swing-rioters had nothing at all; only eighty-five of two hundred and twenty-four on Eliza and twenty-eight of ninety-eight on Proteus admitted having money or valuables.15 If any of the remainder had anything they managed to conceal it from the authorities. Surprisingly men from the notoriously poverty stricken counties north of the Thames Estuary were amongst the best funded men on the Proteus. The largest sum in possession of any arriving Swing-rioter was £40+ held by John Boyes, a Hampshire farmer per Eliza, who apparently brought his return passage money with him in the hope of receiving an early pardon. His optimism was justified for he was freely pardoned on 15 December 1835. He must have been the first transported Swing-rioter to return to England but the date of his arrival has not been found. Thomas Goddard also brought his return fare money with him; enough to buy him a cabin passage per Norval which sailed from Launceston, Van Diemens Land, on 5 June and arrived in England in late November, 1836.

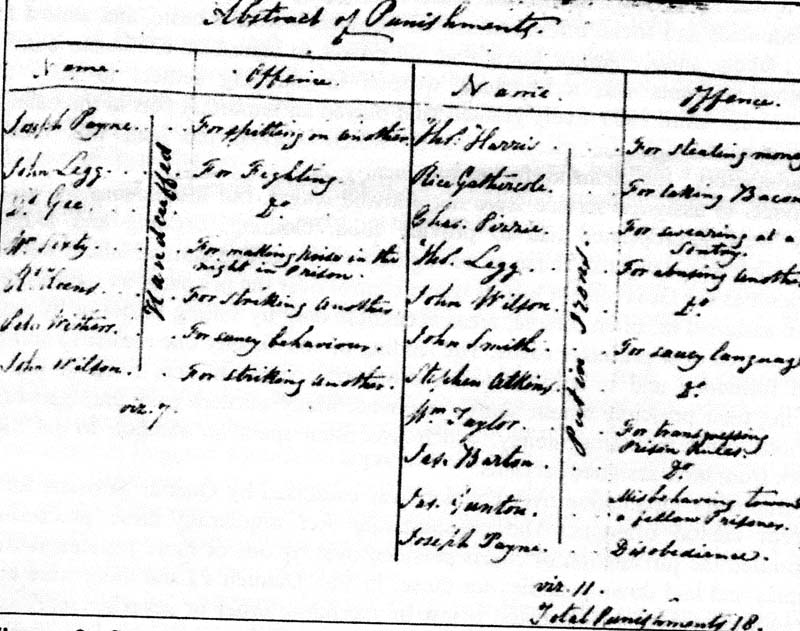

On arrival in Van Diemens Land, Description Lists of male convicts were prepared and information, which included before arrival details and the prisoner's own statement of the reason for his transportation, was compiled for entry on the prisoner's Conduct Record.16 The Description Lists and Conduct Records (See Figures 3 and 4), as valuable to the Convict Department then as they are to the historian today, were instituted by Van Diemens Land's Lieutenant Governor George Arthur who reflected his military training when he required:

... that every convict should be regularly and strictly accounted for, as Soldiers are in their respective Regiments, and that the whole course of their Conduct, - the Services to which they are sent, - and from which they are discharged - the punishments they receive, as well as the incidences of good conduct they manifest - should be registered from the day of their landing until the period of their emancipation or death.

The British Transportation Act specified that every transportee should be accompanied by:

... a certificate specifying concisely the Description of his or her Crime, his or her Age, whether married or unmarried, his or her Trade or Profession, and an account of his or her Behaviour in Prison before and after Trial, the Gaoler's observations on his or her temper and Disposition, and such information concerning his or her Connexions and Former Course of Life as may have come to the Gaoler's knowledge ....

By October 1827 no such document had been sent with any convicts but the Secretary of State, in response to an urgent request from Lieutenant Governor Arthur, then gave instructions that Surgeon-Superintendent's lists of convicts (which included the required information) be delivered on arrival of the relevant convict transport.17

The Swing-rioters arrived in Australia during the period of the assignment system under which convicts were appropriated to government or private service. In Van Diemens Land artisans were sent to Public Works from which the Loan Gang (a group of artisans who were 'loaned' for stated periods to deserving institutions or individuals) was drawn. In the period 1832 to 1838 Swing-rioter masons, bricklayers, brick-makers, carpenters, sawyers and other artisans from the Loan Gang were assigned for up to six months to:

- the Reverent R. Drought of Green Ponds,

- Joseph Archer of Panshanger (to whom John Tongs, Swing-rioter per Eliza, was an assigned servant),

- William Archer of Brickendon,

- William Roadknight of Hamilton,

- William Lyne of Great Swanport,

- the artist, John Glover, of Patterdale (to whom Isaac Hurrell, Swing-rioter per Proteus, was an assigned servant),

- Talbot of Malahide,

- Peter Lette of Curraghmore,

- Alex Denham of Black Marsh,

- Thomas Triffitt and James Mackersey of Green Hill, Macquarie River,

- James Sprent and District Constable Swift, of Hobart Town,

- the Van Diemens Land Establishment at Cressy,

- R.W. Loane of Eastern Marshes,

- Major de Gillern of Glen Ayr, Coal River,

- J.H. Cox of Clarence Plains and

- Others reckoned to be deserving of their services.

Swing-rioters who remained with Public Works generally received fair treatment but those who went to the Loan Gang were probably more favourably treated. The special skills they possessed made them highly valuable and they were likely to be rewarded by the settlers to whom they were loaned for useful work performed. Few were punished for offences and even fewer received corporal punishment. George Coleman, one of the gang on loan to a Mr. Hepburn of Great Swanport, was given fifty lashes for neglect of duty and unspecified misconduct but he was assigned in a remote area where undeserved punishments were likely to escape scrutiny. All corporal punishments had to be witnessed by the local Government Medical Officer; in the specified case the Quaker, Dr. Storey, who hated the duty his position required him to perform.

Farm labourers, tradesmen and others not required for Public Works were appropriated to free settlers and pastoral, or other, companies. Appropriation lists for Eliza, Proteus, Gilmore and Lord William Bentinck and Lotus and York, all of which had at least one Swing-rioter aboard, have survived.18 Eliza men went to John Sinclair, James Parker, John Cassidy, Joseph Bonney, James Hobler, Joseph Archer, Thomas Reiby and others in northern Van Diemens Land, to the Orphan School, Major Lord, Robert Mather, Superintendant of Convicts Josiah Spode and others in the south and to George Meredith and others on the east coast. Proteus men went to John Sinclair, James Parker, Joseph Bonney and others in the north, to Mrs. Bridger and others in the south and to George Meredith and others in the east. Convicts not appropriated to Public Works were assigned for service to free settlers or to one of a variety of organizations such as the Van Diemens Land Pastoral Company which had extensive estates at Woolnorth, Circular Head, Emu Bay and Hampshire and Surrey Hills in north-western Van Diemens Land where the estate managers were forever on the lookout for suitable rural labourers and artisans as convict assigned servants.

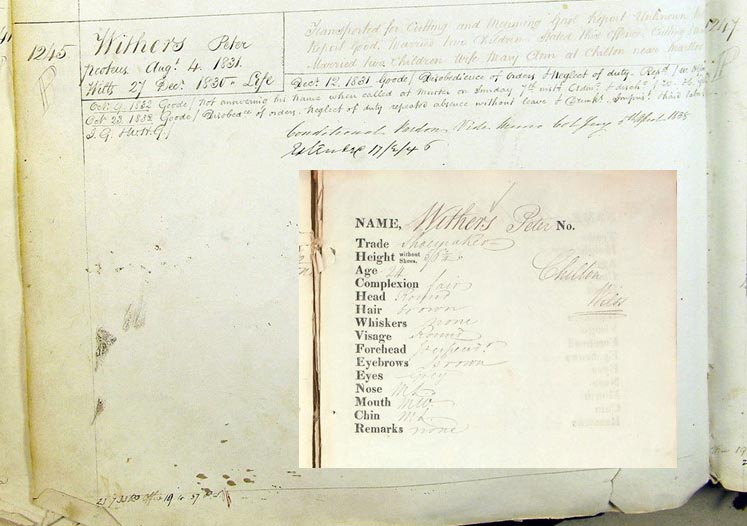

The Court of Directors of the Van Diemens Land Company learnt about the Swing-rioters before they left England through its Chairman, Joseph Cripps, who was also Chairman of Gloucester Quarter Sessions which sentenced twenty-four of the Swing-rioters to transportation. Another Court member, John Pearse, was a Member of Parliament with a Berkshire Constituency from which twenty-six Swing-rioters were transported. Acting on behalf of the Court of Directors Cripps and Pearse submitted lists of transported Swing-rioters recommended· for assignment to the company estates (See Figure 5).19 What the directors wanted was to get at least fifty of the Swing-rioters; mainly farm-workers, but with a sprinkling of blacksmiths and carpenters, hand-pick them in England (straight from the dock in the case of the Gloucestershire men) put them aboard the first convict ship carrying Swing-rioters to sail, and have them landed at Launceston in Van Diemens Land where they could be conveyed at greater convenience than from Hobart to the company's various depots which were nearly all located in north-western Van Diemens Land.

The directors' requests were highly irregular, to say the least, but they were hopeful of success and their company actually achieved a great deal of what they wanted. However the Colonial Secretary would not hear of any prior selection by the company in England, though he approved of a quota of fifty and suggested that Lieutenant Governor Arthur might perhaps allow them, as a first instalment, twenty of the Eliza men included in their original list. Arthur, for his part, though accepting the quota proposed (he could hardly do otherwise) reserved his own right to allocate the men of his choice.

Edward Curr, the Company Manager at Circular Head, also put a spanner in the works by arguing that only twenty-five men could be immediately accommodated (he was short of meat and flour) and, anyway, he preferred an eventual quota of forty rather than fifty men. So as a start the company got twenty-five men from the Eliza and only ten of these (all of whom were Gloucester men) were on the Directors' original list of fifty. Pearse's nominees from Berkshire didn't even surface as possibilities because there were only four Berkshire men on the Eliza; the remaining forty of forty-four sentenced in that county going to New South Wales on the Eleanor.

Twenty-five Eliza men were eventually allotted for assigned service with the Van Diemens Land Company and a further twenty-five convicts were allotted on the arrival of the transports Proteus and Argyle in April 1831 but owing to some confusion on the part of the company's Launceston agent they were refused and later assigned elsewhere.

In Van Diemens Land information from the ships' surgeon-superintendents' reports and other available records was supplemented with further details obtained from the prisoners themselves to facilitate production of conduct records and description lists (See Figures 3 and 4) for use during the prisoner's period of incarceration.

In Van Diemens Land Lieutenant Governor Arthur recognized that self-interest alone would make assignment work and was therefore concerned to see that it was sufficiently to the free settler's advantage for them to put up with its inadequacies and social offensiveness. As convicts were the basic, and almost the only, labour supply Arthur knew that his power to refuse or confiscate convict assigned servants was a trenchant weapon in inducing settlers to obey the regulations. Until 1831 freely granted land played an important part in the balance and, even though the assigned labour which worked the land was mostly unsatisfactory, the demand for it was nearly always greater than the supply. Convicts in assigned service were not allowed wages, but the persons by whom they were appropriated had to provide food, clothing, bedding and lodging according to a standard. Abuse of the regulations governing convict labour was not difficult as the Government lost its direct control over the prisoners as soon as they were assigned to, often remote, areas accessible only by sailing vessel or by many days march over primitive roads. The lending of convicts by one master to another was forbidden and is unlikely to have occurred since masters lived in fear of having their principal labour source removed. Many masters gave indulgences of various kinds including money, which was often spent on alcohol, to get more work from their assigned servants.

Summary jurisdiction over convicts was exercised by Quarter Sessions for all except capital offences. The consolidating Act regulating these proceedings delimited the jurisdiction of courts presided over by one or more justices, defined crimes and laid down penalties for those. In Van Diemens Land there were eight categories of punishment: listed below in ascending order of severity:

- Reprimand,

- tread wheel,

- hard labour by day and solitary confinement by night,

- solitary confinement on bread and water,

- hard labour on the roads,

- the lash,

- work in a chain gang and

- confinement at a penal settlement.

It was intended that there should be a standard punishment for each offence committed by a convict under sentence and that no complaint could be heard more than forty-eight hours after the offence was committed unless the offender could not be found; that is he or she had absconded. Thus, as far as punishment went, an attempt was made to meet one of the main criticisms of assignment, that because it made use of a relatively unknown factor, the private master, it was bound to be unequal in its application, and sometimes too lenient in terms of contemporary standards. Many instances of convicts being admonished appear on their conduct records and it is assumed the magistrates used that 'punishment' when the offender appeared before him more than forty-eight hours after the relevant offence was committed.

The information later entered on the convict's Conduct Record was generally consistent with Arthur's recommendations, but information relating to issue of tickets-of-leave was not always included and reference to later Colonial sentences was usually added as a marginal note, unfortunately often obliterated by tight binding of the records. Description Lists and Conduct Records of female convicts are in separate volumes to those of male convicts.20

Figure 2. Surgeon-Superintendent Logan's list of prisoners punished for

misdemeanours on the voyage of the Proteus.4

| Transport and (Identifying Code) | Loaded at | When Sailed | When and where arrived | Felons/ Rioters aboard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eliza | Portsmouth | 06/02/1831 | 25/05/1831, Hobart Town, VDL | 0/224 |

| Eleanor | Portsmouth | 19/02/1831 | 26/06/183 l, Sydney Cove, NSW | 3/133 |

| Camden | London | 28/03/1831 | 25/07/1831, Sydney Cove, NSW | 197/1 |

| Proteus | Portsmouth | 14/04/1831 | 04/08/1831, Hobart Town, VDL | 112/98 |

| Mary | Woolwich | 12/06/1831 | 19/10/1831, Hobart Town, VDL | 148/1 |

| Larkins | London | 13/06/183 l | 19/10/1831, Hobart Town, VDL | 279/1 |

| Lord Lyndoch | Sheerness | 25/07/1831 | 18/11/1831, Hobart Town, VDL | 266/4 |

| Surrey | Portsmouth | 17/07/1831 | 26/11/1831, Sydney Cove, NSW | 198/2 |

| Gilmore | London | 27/11/1831 | 22/03/1832, Hobart Town, VDL | 222/1 |

| Isabella | Plymouth | 27/11/1831 | 15/03/1832, Sydney Cove, NSW | 222/2 |

| Portland | Portsmouth | 27/11/1831 | 26/03/1832, Sydney Cove, NSW | 175/3 |

| John | Downs | 07/02/1832 | 08/06/1832, Sydney Cove, NSW | 199/1 |

| Lord William Bentinck | London | 07/05/1832 | 28/08/1832, Hobart Town, VDL | 184/2 |

| Planter | Portsmouth | 16/06/1832 | 15/10/1832, Sydney Cove, NSW | 199/1 |

| Parmelia | Sheerness | 28/07/1832 | 16/11/1832, Sydney Cove, NSW | 199/1 |

| York | Plymouth | 0l/09/1832 | 29/12/1832, Hobart Town, VDL | 198/2 |

| Lotus | Portsmouth | 13/12/1832 | 16/05/1833, Hobart Town, VDL | 214/2 |

| Captain Cook | Portsmouth | 05/05/1833 | 26/08/1833, Sydney Cove, NSW | 225/5 |

| 3240/484 |

Table 1. Total Known Swing-rioters transported to Australia by transport vessel

| Transportees | Pre-Sentence Occupations |

Artisan | Other Trade | Agricultural Labourer | Unskilled or unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eliza, Eleanor and Proteus Swing-rioters |

Number | 54 | 78 | 316 | 7 |

| Percentage | 11.9 | 17.1 | 69.5 | 1.5 | |

| Red Rover common felons | Number | 15 | 81 | 52 | 18 |

| Percentage | 9 | 48.1 | 31.3 | 10.8 | |

| Lord Lyndoch common felons | Number | 13 | 91 | 69 | 89 |

| Percentage | 5 | 34.7 | 26 | 34 |

Table 2. Pre-sentence occupations of transported Swing-rioters and

common felons by transport vessel

| When put on list | Age | Name | Disease | When put off list |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 April 1831 | 26 | Timothy Toughill | Ulcer on the glans prepuce | 22 May |

| 7 April | 24 | James Sargent | Gonorrhoea | 10 May |

| 7 April | 27 | James Jeffiies | Catarrhus | 10 April |

| 11May | 30 | William Kennedy | Obstipatio | 13May |

| 17 June | 29 | William Hall | Contusis | 23 June |

| l18 June | 28 | George Atkins | Phlegmon | 24 June |

| 11 July | 30 | Sergeant Brookes | Scorbutus | 14 August |

| 18 July | 29 | George Walter | Sore | 26 July |

| (11 further cases) |

Table 3. Extracts from the daily Sick-book of the Guard of the

Proteus.4

| When put on list | Age | Name | Disease | When put off list |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 April 1831 | 39 | Giles More | Sore | 24 April |

| 6 April | 32 | Tho' Gregory | Catarrhus | 20 May |

| 8 April | 20 | John Simon Clark | Catarrhus | 1 May |

| 8 April | 24 | Robert Cotton | Sycosis Menti | 20 July |

| 9 April | 21 | John East | Catarrhus | 12 April |

| 10 April | 16 | Jeremiah New | Catarrhus | 13 April |

| 10 May | 20 | John Simon Clark | Phthysis | 8 August |

| 5 June | 33 | Will Bloomfield | Obstipation: more or less ill all the voyage | 5 June |

| 8 June | 24 | Robert Lincoln | Obstipation: more or less ill all the voyage | |

| 9 June | 34 | Richard Keens | Diorrhoea | 12 June |

| 17 June | 38 | John Annetts | Cephalia | 22 June |

Table 4. Extracts from the daily Sick-book of the Prisoners per Proteus.4

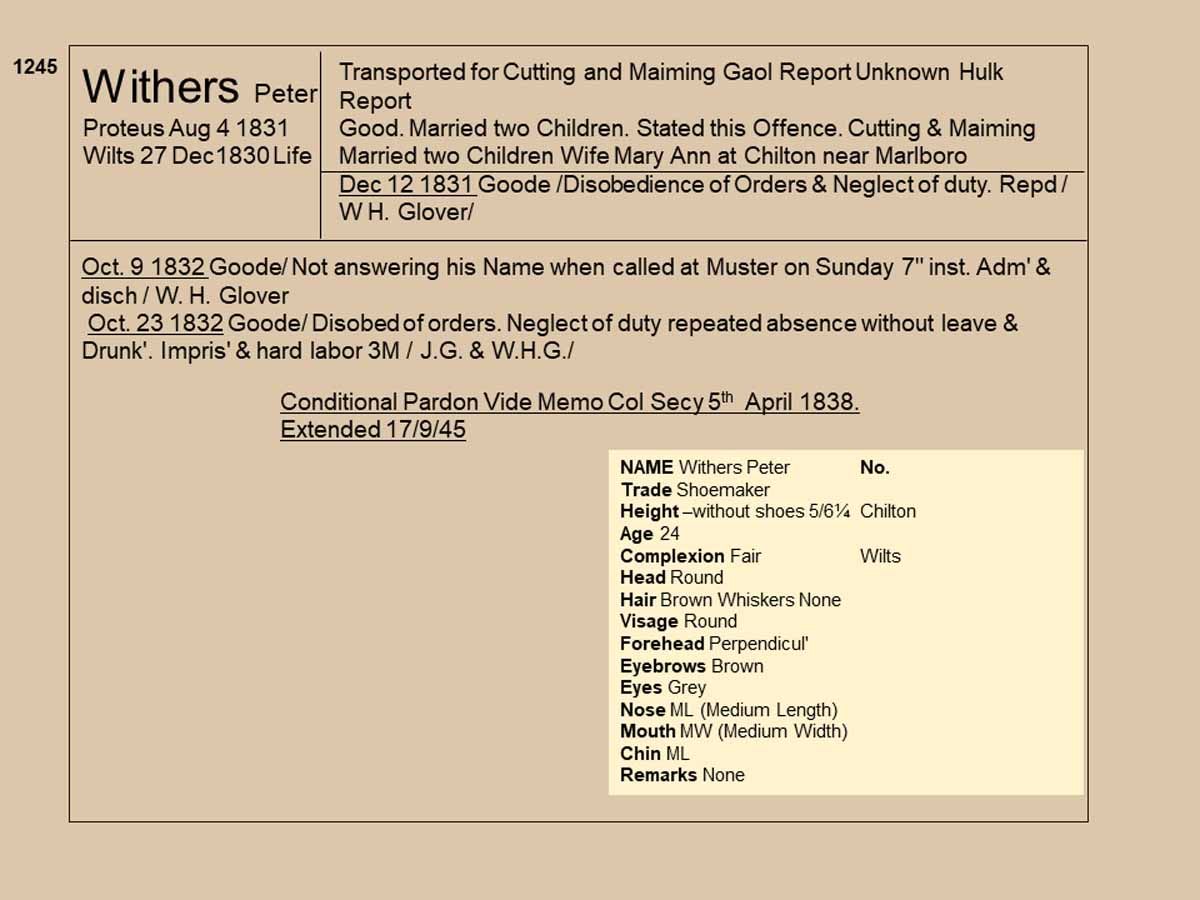

Figure 3. Conduct Record of Peter Withers per Proteus, with his

Description List superimposed

Figure 4. Interpretation and explanation of Conduct Record and Description List of Peter Withers in Figure 3, above.

Figure 5. Lists of Swing-rioters recommended by Directors John Pearce

and Joseph Cripps for assignment to the Van Diemens Land Company

| Name Tasmanian Archives CO 280/36) |

County | Name | Banked | Name (Tasmanian Archives CSO 1/539) |

Valuables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACRES, William | Essex | AKERS, W. | £2/-/-- | AGGAS, William | £2/-/-- |

| BARNES, Francis | Norfolk | BARNES, F. | 12/-6 | As CON 13/4 | 12/-6 |

| BURGESS, William | Hants | BURGESS, W. | 8/-- | As CON 13/4 | 8/-- |

| BUTLER, William | Bucks | BUTLER, W. | £1/10/-- | As CON 13/4 | £1/10/-- |

| COLEMAN, George | Hants | As CON 13/4 | 6/-- | As CON 13/4 | 6/-- |

| CROSS, James | Essex | CROSS, J. | 8/-- | As CON 13/4 | 8/-- |

| DOVE alias DOW, William | Norfolk | DOVE, W. | £5/--/-- | As CON 13/4 | £5/--/-- |

| EVERETT, Thomas | Suffolk | EVERETT, Thomas | 6/8 | EVERITT, Thomas | 6/8 |

| FREEMANTLE, Nicholas | Hants | FREEMANTLE, N. | 17/- | As CON 13/4 | 17/-(+ a watch) |

| GODDARD, Thomas | Wilts | GODDARD, Thomas | £20/--/-- | As CO 280/36 | £20/--/-- |

| GOODMAN, Thomas | Sussex | GOODMAN, Thomas | £4/-/-- | As CO 280/36 | £4/-/-- |

| HURRELL, Isaac | Norfolk | HURLE, Isaac | £1/17/-6 | As CO 280/36 | £1/17/-6 |

| KEEBLE, Robert | Essex | KEEBLE, Robert | £8/-/-- | As CO 280/36 | £8/-/-- |

| KIMMENCE, Robert | Suffolk | KIMMEN, Robert | £1/-5/-- | As CO 280/36 | £1/-5/-- |

| KINGSHOTT, John | Hants | KINGSHOTT, J. | £10/10/- | As CO 280/361 | £10/10/- |

| LINCOLN, Robert | Norfolk | LINCOLN, Robert | £11-1- | As CO 280/36 | £11-1- |

| LUSH, James | Wilts | No entry | LUSH, James | (a gold ring) | |

| MILLER, Isaac | Wilts | As CON 13/4 | 12/-- | As CON 13/4 | 12/- |

| MOORE, Giles | Suffolk | As CON 13/4 | £1/17/-6 | MORE, Giles | £1/17/-6 |

| POTTER, Cromwell | Suffolk | As CON 13/4 | 14/-- | Potter, Cromwell | 141/-- |

| ROSE, George | Hants | ROSE, George | £3/--/-- | As CON 13/4 | £3/-/-- |

| SCOTCHINGS, William | Bucks | SCUTCHING, W. | £1/--/- | As CON 13/4 | £1/--/- |

| SHIP, Stephen | Suffolk | As CON 13/4 | £1/-7/-6 | As CON 13/4 | £1/-7/-6 |

| THORNE, John | Wilts | As CON 13/4 | 11/-- | As CON 13/4 | 11/-- |

| TOOMER, George | Wilts | TOONER, George | 13/-- | As CON 13/4 | 13/-- |

| TURNER, Moses | Bucks | As CON 13/4 | £6/--/-- | As CON 13/4 | £6/--/-- |

| WILLIAMS, William | Suffolk | WILLIAMS, William | £1/-7/-6 | As CON 13/4 | £1/-7/-6 |

| Total for Agricultural Rioters | £75/-7/-2 | £75/-7/-2 | |||

| 70 OTHERS | Various | No entries | Two Not Rioters | 19/-- | |

| TOTAL for PROTEUS | (£70.38) | £76/-6/-2 |

Table 5. Returns of money and valuables by Proteus convicts 04 Aug 1832.17

1. Chambers, Jill, Essex Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth, Hertfordshire, 2004, p 191.

2. Indent of male convicts, Proteus, 4 Aug 1831, Tasmanian Archives, CON14/1/3.

3. Chambers, Jill, Kent Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth, Hertfordshire 2006, Vol. II.

4. Surgeon's Report, Proteus, Tasmania Archives, Admin. 101/62 Reel 3208.

5. Cited by Chambers, Jill, in Rebels of the Fields, self published, Letchworth, Hertfordshire,1995, p 83.

6. Conduct Record, John Simon Clarke, Tasmanian Archives, CON31/1/7 p 97.

7. Chambers, Jill, Hampshire Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth, Hertfordshire,1996, 2nd edn. p 140.

8. Chambers, Jill, Wiltshire Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth, Hertfordshire, 1993, Vol. II p 152.

9. John Moody, Conduct Record, Tasmanian Archives, CON31/1/30 p 57.

10. Stephen Moon, Conduct Record, Tasmanian Archives, CON31/1/30 p 56.

11. Conduct Record, Charles Dunnett, Tasmanian Archives, CON31/1/10 p 52.

12. Conduct Record, Peter Houghton, Tasmanian Archives, CON31/1/10 p 87.

13. Conduct Record, William Rogers, Tasmanian Archives, CON31/1/37 p 59.

14. Conduct Record, George Jenman, Tasmanian Archives, CON31/1/24 p 69.

15. Return of Cash and Valuables for Eliza and Proteus, Tasmanian Archives, CO 280/36 pp 106-16; Assignment list of 112 Convicts per Proteus, 12 Apr 18321, Tasmanian Archives CON13/1/4 pp 8-11.

16. Description Lists of Male Convicts, Tasmanian Archives, CON18; Conduct Registers of Male Convicts arriving under the Assignment System, Tasmanian Archives, CON31.

17. Eidershaw, PR, Guide to the Public Records of Tasmania, Section 3, Convict Department, Tamanian Archives, 2003 Available online at https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-3003662935.

18. Appropriation List of Convicts, Tasmanian Archives, CON27/1/5, CON27/1/6.

19. Mitchell Library CY1195 or CY1278.

20. Description List of Female Convicts, Tasmanian Archives, CON19; Conduct Registers of Female Convicts arriving in the Period of the Assignment System, Tasmanian Archives, CON40.