Chapter 1. The Riots and Trials

You will see your friends and relations no more.

The land which you have disgraced will see you no more. The friends with

whom you are connected will be parted from you forever in the world.

-Mr Justice Alderson, Berkshire Special Commission

The riots appear to have begun at Orpington, Kent, on the first day

of June 1830 when a fire, apparently set by an incendiary, destroyed a wheat

rick and spread to a nearby barn which was destroyed together with other

outbuildings. Another, more serious, fire occurred at Orpington five days

later and, a week after the first fire, notice of a £50 reward upon

conviction of the person responsible for each fire was posted. A seventeen-year-old youth was later charged with setting those and other fires but he

was acquitted after it was convincingly shown that the evidence implicating

him was entirely circumstantial and largely produced by a person of very bad

character.1

In East Kent there were reports of a machine breaking episode, in which about twenty-five men were thought to have taken part, at Wingmore on the evening of 25 August 1830 and threshing machines were destroyed in the Lower Hardres area, north of Wingmore, on the night of 28 August and in the Lyminge area to the south on the following night. Military aid to quell rioting and machine breaking in the Lower Hardres area became necessary and a squadron of Dragoon Guards was despatched there from Canterbury on 30 August 1830. Burning, machine breaking and rioting episodes continued sporadically until mid December 1830 making Kent one of the counties longest affected by the Swing riots.

Meanwhile, on 16 October 1830 at Battle in East Sussex, William Cobbett addressed an audience of five hundred, many of whom were labourers. Cobbett began his address with reference to the fires in Kent which he predicted would spread to Sussex if the labourers' grievances were not met; a prediction proved correct by the occurrence of a hay rick burning at Hartfield, East Sussex, on the following night and by further fires in November. Initially the labourers in East Sussex gained a little by negotiation but the disturbances there - incendiarism, machine breaking and rioting - soon followed the pattern of Kent and, in the second week of November 1830, the riots reached West Sussex. Meanwhile there had been a slower northward spread from Kent of mainly arson episodes the first of which occurred in the Essex parish of Beauchamp Roding on 4 November 1830.

In Hampshire Swing letters threatening to destroy property were received in early November 1830 and threats of arson were promptly followed up. Mobs gathered to hold meetings demanding higher wages for farm labourers and to make levies on households and passers by. Machine breaking began in Hampshire in earnest on 18 November when the mob broke at least nine threshing machines in a single day. One hundred and fifty special constables were sworn in at Portsmouth and a hundred men of the 47th Regiment were moved from Portsmouth to Cosham but the arrival of the troops and the presence of special constables seemed only to increase the breakers' determination.2 The pattern of rioting - machine breaking followed by demands for money, food or beer - continued, virtually unabated, to mid December just before the Hampshire Special Commission, which opened in Winchester on 20 December 1830.

Early in the riots demands for reductions in tithes were added to

the labourers' peremptory requests presumably because the farmers had told

them that they could only afford to increase their wages if the tithes were

reduced. On 20 November 1830 the mob moved beyond breaking machinery for the

abridgement of agricultural labour by adding Tasker's Iron Foundry at

Andover to the targets attacked.

Rioting and machine breaking began in

Wiltshire (the county most affected by the riots) almost simultaneously with

the risings in Hampshire.3 Swing Ietters were sent to farmers and

manufacturers threatening destruction of their property if they failed to

remove machinery or to raise wages, stacks and barns were fired and there

were riotous assemblies and demands were made for higher wages and

reductions in the tithes.

In Berkshire John Briginshaw, a farmer in the Parish of Bray received an anonymous letter on 10 November which read:

I tell you Mr Bridgshaw either be hook or by crook your life hor Blood hor Bread - Wm Baaker - Wm Headington - fread Winkworth, Mr Lobb, Mr Alaway, Mr Wender, Mr Shasel, Mr Mortimore, Blood hor Bread or 12s - 15s.4

Rick

burning, machine breaking and further arson attacks began a couple of days

later but there were probably fewer arson episodes in Berkshire than in some

other counties. As in Hampshire the breaking was not confined to

agricultural machinery; at Hungerford other machinery and wrought iron

articles were destroyed at an iron foundry belonging to Richard Gibbons.

In Buckinghamshire arson attacks began near the Berkshire border early in November and machine breaking began in earnest in the village of Stone on 25 November 1830 but at High Wycombe a new dimension, the destruction of papermaking machinery, was added.5 Summoned by the sound of a horn about fifty papermakers and their supporters armed with sledge hammers, crow-bars, pickaxes and clubs, gathered in Flackwell Heath at five o'clock in the morning of 29 November and marched in search of paper making machinery. As the mob passed through High Wycombe they were seen by the Chief Constable who hastily summoned such help as he could find (possibly limited to one special constable; at least one other refused to help) and immediately made for Lane's paper mill, which he suspected was about to be assailed. He reached the mill before the rioters did and was able to warn the management of the forthcoming attack which they were unable to repel in spite of firing on the rioters and throwing vitriol over them.

Having destroyed machinery in

Lane's mill the mob proceeded to destroy machinery at another paper mill

before breaking a threshing machine and then machinery in two more paper

mills. While machinery was being broken at the last mill attacked - the

Snakely Mill at Loudwater - reinforcements arrived for the hard pressed

Chief Constable, who had so far managed only to gather up a few rioters who

were injured and disabled. The machine breaking ended at that stage and a

number of arrests were made but the greater part of the mob, now reckoned to

be at least two hundred, ran away. Papermaking machine breaking was not

confined to Buckinghamshire; paper mills were also later attacked at

Colthrop in Berkshire and at Lyng and Taverham in Norfolk.6

Before the end of 1830 more than twenty southeast of England counties were affected by the riots and in Suffolk the farm labourers decided to try strike, rather than direct, action in an effort to improve their living conditions. On 6 December 1830 the Reverend William Mayd and another Withersfield (Suffolk) magistrate were signatories to a letter, which said in part:

My Lord,

A Disturbance has this day commenced in the parish of Withersfield - the

labourers have all struck for wages, and threatened to take the farmers corn

by force, similar disturbances have arisen in other neighbouring parishes

... .7

At that time trade unions were legal but strike action remained

illegal in England until 1875. Withersfield is in Suffolk, just across the

Suffolk-Essex border, and the rioting had spread northwards to Essex from

Kent only a few weeks previously. The Swing movement had now closed a great

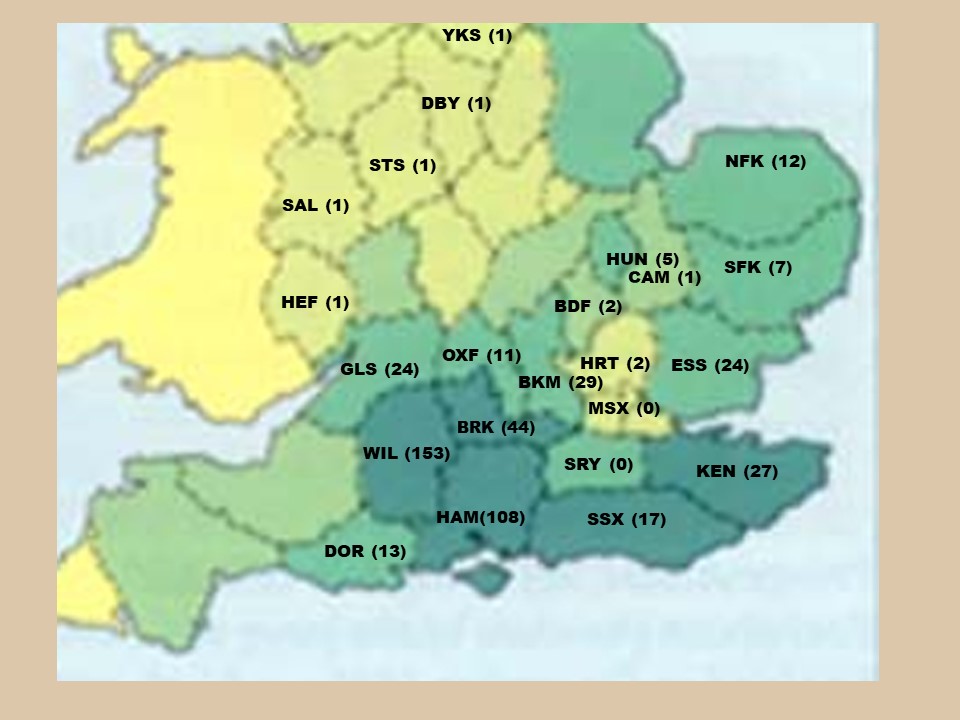

circle from Kent to Essex (Figure l below) affecting more than twenty

southeast of England counties. Only London and the already greatly urbanised

Middlesex had no rioting or machine breaking episodes but some natives of

both London and Middlesex who had moved to reside in, or were employed in,

other parts of southeast England played active roles in the riots.

When it became obvious to the authorities that there was a great deal of sympathy for the Swing movement and that it was spreading rapidly a tougher approach than that adopted by the County Court Sessions became necessary and Special Commissions were constituted in the worst affected counties to try the rioters many of whom were already in overcrowded county gaols awaiting trial. The Special Commissions, in which the rioters were tried before a Grand Jury, began in Hampshire on 18 December, Berkshire and Wiltshire on 27 December 1830, Buckinghamshire on 10 January and Dorset on 11 January 1831. The proceedings of those commissions which were characterised by the extreme savagery of the punishments they inflicted, especially on offenders who were not farm labourers, are well reported in a series of accounts by Jill Chambers as is evident from the following.

John Tongs, a Hampshire

blacksmith with a wife and five children, took part in a machine breaking

episode at Hall Farm at Michelmersh in Hampshire early in the riots. He and

Arthur Fielder, who participated in the same episode, volunteered

confessions to the farmers in the parish who all expressed a readiness to

forgive. The two men did not know of their pending prosecution until two

days before the beginning of the Hampshire Special Commission at which they

were tried together with John and George Collins and George Palmer. In

finding the five men guilty the Jury begged to recommend them to mercy on

account of their previous good behaviour and the excitement of the times but

both were included, with sixteen others, in a group all of whom were

sentenced to be transported to Australia for seven years.

Thomas Goddard, a prosperous Ramsbury (Wiltshire) tanner, rode a horse to the scene of a machine breaking episode at Aldbourne on 23 November 1830 where he said he thought his presence might prevent the mob from doing mischief. The rioters broke a threshing machine and demanded a sovereign from its owner, Richard Church, who asked to whom the money should be given. The machine breakers called for George Durman but he did not appear so they asked for the sovereign to be given to Goddard who later passed it to Durman. Goddard and William Taylor, the machine breaker who demanded the money from Richard Church, were charged by the Wiltshire Special Commission with robbing Church of a sovereign and both were found guilty but recommended to mercy. Goddard was apparently present at other episodes during the Swing Riots because he was charged, with sixteen others, with riotous assembly and beginning to demolish the house of Robert Pile at Alton Barnes on 23 November 1830 and with robbing John Clift in another episode on the same day but he was not tried on the first of those charges and found not guilty on the second. Thomas Goddard and William Taylor, together with ten others were sentenced by the Wiltshire Special Commission on 11 January 1830; Goddard and Taylor each to seven years transportation. After Goddard protested that he was innocent he was addressed by Mr Baron Vaughan as follows:

I cannot allow you, Thomas Goddard, to depart from the bar without stating, that though it is clear that you were not the ringleader of your party, we are willing to hope that you continued with them longer than you otherwise would have done under the notion that your presence might prevent personal violence. Yet, as considerable encouragement was given to the mob by your presence and aid, it is impossible that we can avoid inflicting on you severe punishment. You must be transported for seven years.3

John East was employed as a letter founder in High Wycombe and left his work to follow the mob accompanying the machine breakers as they marched through High Wycombe on 29 November 1830. East came of a papermaking family and his wife Charlotte, nee Blizard, the mother of his infant son, was a paper maker. None of his family appears to have been amongst the rioters but their leader, Thomas Blizzard, may have been related to East's wife. East was arrested without a weapon, or even a stone, in his possession when he came forward to face the newly arrived special constables as the breakers were about to enter the Snakely Mill at Loudwater. In giving evidence the special constable who arrested him stated that 'He was fighting his way through the crowd to face the special constables. He had nothing in his hand and when he came up to us so I took him into custody'. John East presumably gave himself up but had he ran, as most of the rest of the mob did, he would probably not have been caught. The first time he appeared before the Buckinghamshire Special Commission he was acquitted because of lack of convincing evidence against him but he was put back in the dock the following day and sentenced to seven years transportation after Mr Justice Patteson had ruled that:

all persons present at these proceedings and not interfering to put a stop to them, become parties to the offence, and are liable to transportation.5

East remained in Australia and remarried after he was pardoned. He never saw his first wife again and possibly never held their son in his arms as the child seems to have been born while he was in prison awaiting trial.

William Briant, the elder, received a disabling gunshot wound outside Lane's paper mill at Loudwater on the Wye River, (the first Buckinghamshire mill attacked) on 29 November 1830 so was unable to enter the mill with the mob and obviously broke no machinery. He was none-the-less sentenced to seven years transportation for breaking machinery in Lane's and two other mills which the mob attacked after he was disabled. An unsuccessful petition, signed by sixteen persons, and submitted on behalf of Briant read, in part:

That your Petitioners hopes and prays for a mitigation of Punishment in

consequence of his not being in any respect active in the Riot but had

unfortunately mixed with the Mob without reflecting on the consequences.

That your petitioner has sustained much punishment for his transgression

having been shot through the right arm although he was not within four yards

of the Mill when wounded.5

The Secretary of State, Lord Melbourne, was not impressed. It was also widely, but wrongly, believed that only a small percentage of the rioters and machine breakers had been arrested so the Buckinghamshire Special Commission sentenced everyone they possibly could with small regard for guilt or innocence; Briant being convicted for 'offences' supposed to have been committed at places at which he was not present after he was wounded and in custody.

Isaac Burton, a tailor, was charged with destroying a threshing machine belonging to John Hawkins of the parish of Welford in Berkshire on the evening of 23 November 1830 and also with having feloniously assaulted Hawkins and robbed him of two sovereigns. Burton was accompanied by twenty to thirty other men, was not one of those identified breaking the machine and interceded to prevent the mob from entering Hawkins's house. He was acquitted of the second charge on which he was tried but was none-the-less sentenced to seven years transportation.4

When the special commissions and county sessions had finished their work over a thousand convicted persons were in custody in unsanitary, overcrowded prisons or on equally odious hulks. A few were pardoned, some died in prison or on the hulks and a small number, most of whom were too infirm to be transported, served out their sentence on a hulk but more than four hundred and eighty four were embarked on transports bound for Australia and two on transports bound for Bermuda. The counties of trial of the Australian contingent and the numbers known to have been transported to Australia from each county are shown in Figure 1 (below).

Evidently the county sessions and especially the special commissions had little regard for the families of those transported some of whom did not even get the parish relief due to them as is evidenced by the following extract.

QUEEN-SQUARE - A lad, not more than twelve years of age, was charged by policeman Dawney, of the B division, with an offence which has been frequently considered at this office as of a most dreadful nature, that of being found sleeping in the open air. The policeman stated, that the lad crouched himself under the portico of St. George's hospital, but this situation afforded him very little protection from the rain, which at this time was falling in torrents, and upon the prisoner not being able to give an account of himself he took him to the station-house.

The boy, who shivered with cold when placed before the Magistrates, said that his name was George Fisher. He was born at Beaconsfield, in Buckinghamshire. He did not recollect his mother, but he knew very well that his father had been transported Mr. Gregorie - 'For what offence was he transported?' The boy burst into tears, and said for breaking machinery in Buckinghamshire. Since his father had been transported he had not had a friend in the world He was willing to do all he could for himself, and had come up to London to seek for work. Mr. Gregorie - 'Before you left Buckinghamshire, how did you live?' The lad replied - 'As well as I could. I did jobs; and sometimes slept in the manger and sometimes in the yard Nobody cared about me.' Mr. Gregorie - 'Did you apply to the overseers of the Union workhouse?' I did, but I could get no relief.' Mr. Gregorie - 'To whom did you apply?' 'I went to Hobbs, a publican, at Woburn-green; he is one of the overseers; but before I went there they told me if I hadn't friends it was of no use, and I found it was true, for they would not give me a halfpenny, and so I came by Mr. Jolly's waggon to London'. Mr. Gregorie - 'Did you apply to the Guardians of the Poor?' 'I did not, for I was left without friends, and nobody helped me.'

The policeman, Dawney, said that he was himself born in Buckinghamshire, and having only lately joined the 'Force', he knew, and could swear, that the overseers in that part of the country would not allow a destitute man or woman to be introduced to the Guardians, no matter as to the business they might have with them. Mr. Gregorie ordered the poor lad to receive immediate relief, and that a few shillings should be given to him from the poor-box. He would himself take care that he should be sent back to his parish, and directed the clerk to write to the Union workhouse authorities, in order that he might receive the relief due to him - Weekly Dispatch, Jan. 6, 1839.

Figure 1. Southeast of England counties affected by the Swing riots with the numbers of rioters (in brackets) from each county known to have been sentenced to transportation and transported to Australia by Special Commission or County Session. There were no prosecuted riot episodes in Middlesex or Surrey but some natives of those counties who had moved temporarily or permanently to other counties were amongst the rioters prosecuted elsewhere.

The c group includes Kent and Sussex;

the e group

Cambridge, Essex, Hertford, Huntingdon, Norfolk and Suffolk;

the m group

Bedford, Buckingham, Derby, Hereford, Oxford, Shropshire, Stafford and

Yorkshire

and the u group Berkshire, Dorset, Gloucester, Hampshire and

Wiltshire.

1. Chambers, Jil, Kent Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, Vol. I. 2006.

2. Chambers, Jill, Hampshire Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, 2nd edn. 1996.

3. Chambers, Jill, Wiltshire Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, Vol. 1. 1993.

4. Chambers, Jill, Berkshire Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, 1999.

5. Chambers, Jill, Buckinghamshire Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, 2nd edn. 1998.

6. Chambers, Jill, Dorset Machine Breakers, self published, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, 2003, Introduction.

7. PRO HO52/10 ff 50-51. Cited by Jill Chambers in Machine Breakers' News 5(3), 1999.